With twenty years of experience in the assistive technology field in training, managing, advocating, and using braille as a sighted user, Andrew Flatres has seen it all: The braille revolution, its challenges, and its positive impact.

To connect the dots, we interviewed Andrew, one of our dedicated experts in the field, to shed light on the impact of braille on education, technology, and employment.

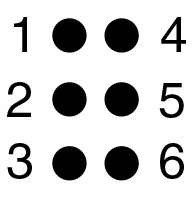

Answer: Braille is not a language but a tactile code that allows people with limited or no vision to read by touch. Each dot or combination of dots, called a braille cell, represents a letter of the alphabet, a number, or punctuation marks and fits perfectly under a human fingertip. Together, they can express words, phrases, equations, musical notation and much more.

Originating as a military code and used for nighttime reading more than 200 years ago, Louis Braille developed the more usable version of Braille at the age of 15. The six-dot cell code that bears his name is an effective communication system now used by the blind community worldwide.

Answer: Some manual tools for reading and writing braille, such as the slate and stylus, wooden games and braillers, have been around for a long time and are still widely used today. More recently, software, portable electronic braille devices have allowed people to write, save, edit, access documents in audio or tactile formats, and produce them in hard copy using a braille printer.

From note takers to braille displays, new trends have emerged, making devices smarter, more convenient, connected and socially inclusive. The BrailleNote Touch; the first Google-certified braille tablet allowing notetaker users to install typical apps and allowing much broader access to that, revolutionized the market in 2016.

Improved braille display capabilities now allow for more important tasks to be accomplished independent of a screen reader. There has never been such a wide range of refreshable braille devices, and as a strong advocate of braille, I am thrilled to see it being used for all kinds of occasions.

Answer: It is disappointing and frustrating to hear such comments. One of the triggers for these assumptions is that mainstream technology is much more advanced and designed with inclusivity in mind, including some form of built-in accessibility.

But the benefits of braille are greater than simply accessing nonvisual information from a screen-reader and audiobook. Like learning to use pen and paper, learning braille plays a vital role in reading and writing skills. It is a way to learn grammar, syntax, spelling, or arithmetic and is a gateway to accessing mainstream information, reading independently, keeping up with schoolwork, and getting or keeping a job. Without it, the risk of becoming illiterate and unemployed increases significantly.

Answer: I foresee great innovations in the braille world. Things like refreshable multiline braille displays to tactile devices are just around the corner. I am excited about this next big step in braille, as I am sure we will soon provide a seamless experience for reading graphics and braille on a single display.

I have had the pleasure of participating in the launch of an impressive number of assistive technologies for people with varying degrees of blindness. Braille technology is breaking new barriers, enabling individuals to perform their daily tasks more efficiently.

Yet the main challenge with electronic braille devices remains affordability. By working with some of the world’s leading innovators and partners, we efficiently produce braille devices without sacrificing reliability and performance.

This is extremely important in places like Africa. HumanWare has been providing donations, trade-ins, and boost ups of assistive technology products for many years. Thanks to the generosity of our kind customers, we are able to bring braille products to some of the less fortunate areas of the world.